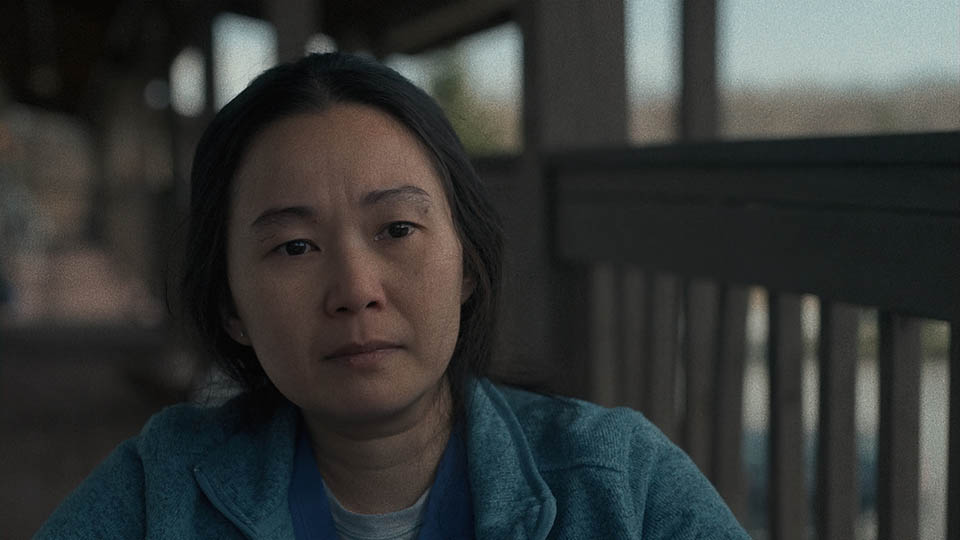

The Whale is directed by Darren Aronofsky. The Film stars Brendan Fraser, Sadie Sink, Hong Chau, Ty Simpkins, and Samantha Morton

If you were anywhere near London’s Southbank Centre last year on the evening of October 11th, you probably heard a cacophonous roar. This was no historic sporting moment nor a massive music festival – it was the noise of a vast crowd rising to applaud Brendan Fraser. His new film The Whale, opening in UK cinemas this weekend, had just premiered to a rapturous reception at the London Film Festival. Many in attendance that night, myself included, quickly posted clips of the standing ovation on social media with the ‘Brenaissance’ – Brendan Fraser’s return to major stardom – soon becoming a trending topic. The film’s publicity campaign has since centred on Fraser’s astonishing (and now Academy Award-nominated) performance, missing a critical factor in The Whale’s success – its power as a piece of empathetic cinema.

Fraser plays Charlie, a man dealing with regret and grief after leaving his wife and daughter for Alan, one of his younger male students. Alan’s death a few years later, however, left Charlie to find comfort in food, with his binge eating driving him towards a level of obesity so severe he requires almost round-the-clock care from Liz, a friendly nurse with a personal connection (a terrific Hong Chau). Much of the media coverage of The Whale and Fraser’s performance has focused on Charlie’s weight (close to 600lb), mainly since it is rare for films to deal openly with such people who are so often forgotten or dismissed within society. But, to its great credit, The Whale never shies away from unflinchingly portraying the challenges that many obese people face. In an early scene, for example, Charlie searches his blood pressure results on Google. He is so overwhelmed by the severity of what he reads (“CALL 911 NOW”) that he returns to something that won’t judge him – he eats three chocolate bars in quick succession before realising that what he’s doing is, quite literally, killing himself. This is a scene that will hit close to home for many. Comfort eating to avoid the pain of the outside world is something I know all too well, having struggled with obesity during my life, although, it must be said, not to Charlie’s extent.

The overwhelming media focus on Charlie’s obesity left me expecting to relate to The Whale since Charlie was facing similar struggles to mine. I have since realised, however, that instead, the film’s portrayal of Charlie is so much deeper than that; the audience eventually views him simply as a man with whom they can empathise rather than sympathise. The screenplay walks the line between specificity and universality deftly – Charlie’s character arc, whilst happening to someone in an exceptional circumstance, is truly universal. He’s a man racked with guilt and regret over his actions which is just trying to make amends. This balance of specificity and universality is one of the film’s most vital advantages and is reflected cinematically to significant effect. Early wide shots highlighting Charlie’s enormous stature, for example, soon give way to far more intimate close-ups, focusing the audience’s attention on his face and forcing them to see Charlie emotionally rather than physically.

However, such techniques would only work with the right actor at the centre. Darren Aronofsky has had tremendous central casting success with Mickey Rourke in The Wrestler and Natalie Portman in Black Swan. These two films are similarly performance-driven, and he has hit another home run with Brendan Fraser. His performance is one of delicate nuance. Something as simple as a glint in his eye or a little nod can express emotions so deeply and clearly. His performance may be enhanced by the inherent ‘everyman’ quality Fraser embodies, but he imbues Charlie with such believable emotion that an audience cannot help but empathise with him. He’s not a man defined by his size suffering through a terrible condition. He’s just a human going through a hard time – Fraser makes the personal universal. So whilst the film does indeed portray the challenges that obese people face every day and inspire sympathy on their behalf, it also reminds us that we are ordinary people with whom everyone can empathise.

It took me three viewings to determine why I’d been so greatly affected by The Whale. Yes, I felt ‘seen’ as someone who’s struggled with obesity and the challenges it brings; yes, I’d witnessed the big-screen comeback of an actor I’d always loved, and yes, I’d been touched by the film’s themes of love and redemption. But I finally realised the most profound reason after my third viewing at a packed preview screening in London. Somewhere behind my seat were sat two sisters audibly gasping at some of the film’s early scenes, particularly those that unflinchingly portray the realities of binge eating. Yet as it continued and the portrayal of Charlie began to shift cinematically and emotionally, I noticed a fundamental change in their behaviour – the gasps were replaced by sniffles and tears. And as the credits rolled, I turned and found them to be in a very emotional state, much like myself.

Legendary critic Roger Ebert wrote that films “are like a machine that generates empathy…a great movie lets you understand what it’s like to be [sic] different…it helps us to identify with the people who are sharing this journey with us”. I cannot think of a sentence to apply here that demonstrates the collective power of cinema I’d just witnessed. I believe one leaves The Whale filled not with sympathy for those who struggle with obesity but with a shifted viewpoint and a new-found empathy for people like Charlie. And that is indeed the power of cinema.